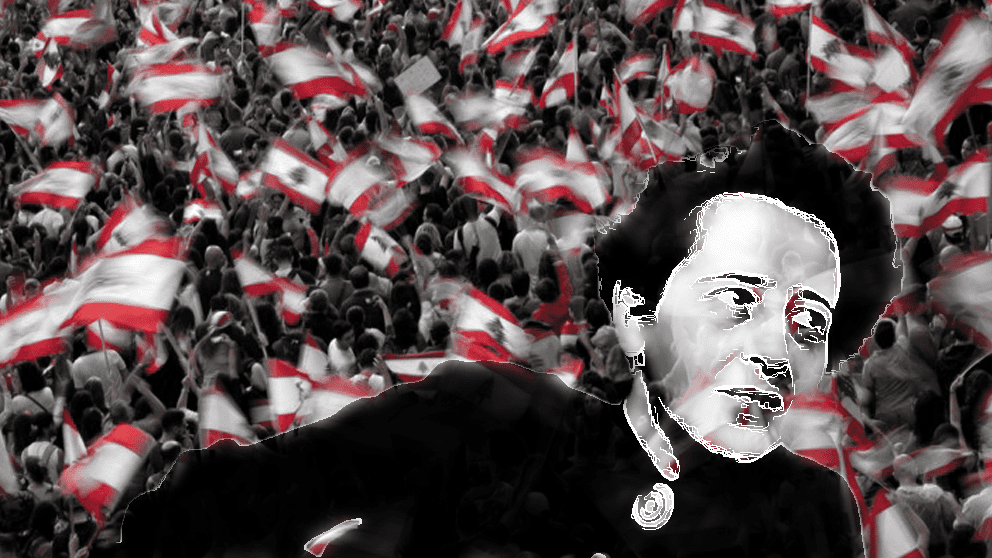

Last weekend, I marched away from the American show of solidarity in Washington Square Park, held on that day in conjunction with global cities popular to the Lebanese diaspora, and I walked up Fifth Avenue toward the Hannah Arendt Center at the New School for Social Research. My silent investment in the German philosopher’s range of works has been my sole weapon of protest.

Her book titles speak for us, and for themselves. Mafia tactics deployed to remove demonstrators from the streets read straight out of Origins of Totalitarianism. Diversity in slogans, including the famed #AllMeansAll, mourn the people’s Human Condition. Calls to transition from sectarianism to secularism seem equally stuck Between Past and Future. Behind-the-scenes governmental picks, or lack thereof, may indeed need a guide for Men in Dark Times or a radical view On Revolution.

She who knew the Nazi regime inside out, how can Hannah Arendt guide the Lebanese Revolution as it stamps a month of struggle? Despite the swap of context, Hannah Arendt’s writings seem to survive the blow of Lebanon’s one-of-a-kind predicament.

None of our political leaders are Adolf Hitler or Joseph Stalin, and yet their rise to power follows closely the footsteps of the group Hannah Arendt calls the mob; rejects of society who, to her, mediocre, and infused with much vanity and little morality, have clutched onto the seats of the throne.

These newly-esteemed politicians, as Arendt chronicles in Origins, have aimed to lure, on the one hand, a select party membership of similarly disenfranchised castaways, tempting them with social value. On the other, they have sought to cut the relations among the rest of society via religious, nationalist rhetoric or disinformation campaigns that pit neighbor against neighbor.

Another tactic to further atomize members of society is rigging with economics. While the Nazis succeeded in drastically reducing unemployment, a scheme that would effectively distract and therefore segregate Germans, the Lebanese political elite could not. Perhaps out of mere incompetence, Lebanon’s elite could only see fit to liquidate whatever was left of a shrinking middle class, buy the complacency of the few it could practically enrichen, and hope that the majority left would be too starved, but not starved enough, to resist.

Hannah Arendt’s microscopic view of the mediocrity of the mob should inform the Lebanese as they continue to call out the incompetence of their politicians –most of whom, as Arendt would see it, now improvise on a script for which they have not prepared. This would in part explain disastrous decisions within political circles, the most recent of which is President Aoun’s speech mishap. Undoubtedly more innovative and surprising protest tactics will further lead politicians to shoot themselves in the foot.

Another concern among the protestors is the fear that political parties are attempting to co-opt and exploit their revolution. Hannah Arendt’s analysis of the French Revolution may be of help.

The French case is fitting because of the many allusions to it on social media, especially among skeptics who are fearful of a similar and potential period of economic demise being institutionalized in the wake of untamed display of passion.

“It was the men of the French Revolution,” Hannah Arendt warns with On Revolution, “who, overawed by the spectacle of the multitude, exclaimed with Robespierre, ‘La Republique? La Monarchie? Je ne connais que la question sociale,’ [The republic? The monarchy? I know the social question] and they lost, together with the institutions and constitutions the soul of the revolution itself.”

The political theorist would have been very happy to observe that the Lebanese, from the most organized civil society group to the least expected vox populi cast on television interviews, are continually calling to remain loyal to the constitution. This approach must be preserved in order to preempt exploitation.

The failure of revolutions is precisely due to its split into two extreme sides, the indulgent and the enragés, who, as Hannah Arendt put it, not merely “worked together to undermine the revolutionary government,” but eventually led to popular acceptance that “the revolution was saved by the man in the middle, who, far from being more moderate, liquidated the right and left as Robespierre liquidated Danton and Hébert.”

That is perhaps Hannah Arendt’s most critical warning for the revolutionaries in Lebanon. Not to pave way for the illusion that the revolution ought to be saved, not by its superheroes like our martyr Alaa, but by another crook disguised as a middle man.