Widely known in the region for its tolerance in terms of freedom of press, Lebanon hosts many journalists in exile from surrounding countries. Yet, numerous challenges on many facets hinder the work of exiled journalists. As a result, they arrive to Lebanon but do not wish to permanently reside in the country.

Surrounded by countries with limited freedom of the press, Lebanon appears to be a safe place for journalists seeking a close refuge to continue their work. Yet, taken out of this context, freedom of expression in Lebanon has major limits. Numerous challenges undermine the exercise of journalism independently, freely and, most importantly, safely.

“I do not feel safe here,” said Syrian journalist Naama al-Alwani. “After receiving too many threats on social media or over the phone, I stopped publishing.”

Al-Alwani expressed her strong desire to leave Lebanon and to continue her job in a safer environment. Despite the existence of distinguished initiatives supporting freedom of expression, both Lebanese and exiled journalists operate in a highly politicized media landscape where sensitive topics should be avoided and threats of violence are recurrent.

“I used to be in danger in Syria and I do not want to be in danger again,” she told Beirut Today.

The Political Landscape and Vague Laws Facilitate Attacking Journalists

Partially because of challenges in terms of politicization, Lebanon ranks 101 of 180 in the 2019 RSF World Press Freedom Index. What Dr. Suad Joseph calls “Political Familism in Lebanon” constitutes a chief obstacle to the development of a free and independent media landscape.

In their detailed report “Lebanese Media – A Family Affair,” the Media Ownership Monitor in Lebanon launched by Reporters Without Borders and the Samir Kassir Foundation exposed the control key political groups and wealthy family clans have over Lebanese media. The key findings indicate a highly politicized media landscape that plays a crucial role in shaping the public opinion.

The Samir Kassir eyes (SKeyes) Center for Media and Cultural Freedom constantly monitors the difficulties facing and violations against journalists in Lebanon and the MENA region.

“If you’re a journalist here and you’re attacked, you can be sure that nobody will hold the person who attacked you accountable,” SKeyes Executive Director Ayman Mhanna tells Beirut Today.

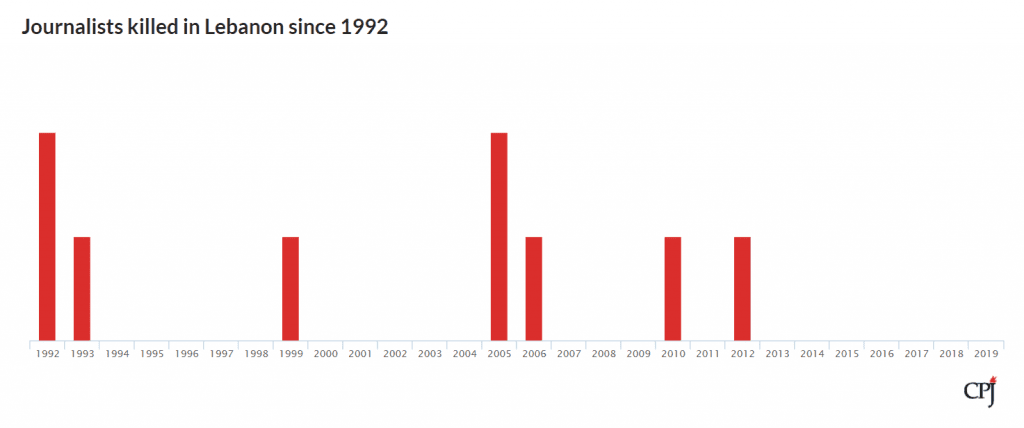

Since 1992, nine journalists have been killed in Lebanon. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), four of these journalists were actively targeted for murder and four of the murders went unsolved. SKeyes itself was founded after the assassination of prominent political journalist Samir Kassir in 2005. His death vividly demonstrates the great risks that journalists face, especially in periods of deep political divide and unrest.

Among others, the Committee to Protect Journalists in Lebanon has denounced the assault by Lebanese soldiers on four journalists covering a protest in Beirut on December 23, 2018.

While those who launch attacks or campaigns against journalists often enjoy impunity and exempt from punishment, journalists in Lebanon suffer through prosecutions based on unclear and arbitrary legislation on freedom of expression.

“Currently, we are facing a period where legal actions are taken very frequently against journalists based on very vague definitions,” said Mhanna.

Since its foundation, Skeyes has promoted the freedom of expression through notable projects like the Samir Kassir Award for Freedom of the Press which, in partnership with the European Union, honors journalists from the region for opinion and investigative articles related to law or human rights.

“The sense of recognition builds journalists’ good reputation, reinforces their self-confidence and encourages them to cope with the difficulties of the journalistic work,” said Roger Asfar, a journalist based in Beirut since 2008 and the winner of the 2019 award in the Opinion piece category. The journalist analyzes “Captain Majed or the Father Commander” in his article, suggesting the need to break away from the concept of heroes instilled in the minds of Syrian children for the development of a genuine democratic society.

Exiled Journalists In Lebanon, Especially Syrians, Live In Constant Fear

Inspiring initiatives like the Samir Kassir Award for Freedom of the Press attempt to counterbalance the recurrent episodes of intimidation. However, independent journalists coming from surrounding countries are only willing to temporarily stay in Lebanon because of the remaining threat and pressure on them from authorities.

“Sadly, the media landscape in Lebanon has gotten worse,” said Ahmad Alqusair, a Syrian journalist inexorably continuing his work as a freelancer in Lebanon. “It is not free for the Lebanese, imagine how it is for Syrians.”

For exiled journalists in Lebanon, a major concern is their safety in the country. For Syrians, the perceived risk is very high.

“The fear primarily comes from the Syrian regime and its involvement to some extent in the Lebanese landscape,” he said. “Both Hezbollah and the Lebanese Security Services constitute major threats to Syrian journalists and activists.”

Consequently, most of Syrian journalists and activists want to leave Lebanon. Many of them have already left for other countries.

Bassel Tawil, a former Syrian journalist and activist now based in Paris, recalls his stay in Lebanon as an extremely nerve-racking period.

“I had lost my wallet so I got into the country without documents. At the many checkpoints around the country, anyone could stop me and send me back to Syria where I’m wanted by the Syrian regime,” said Tawil.

Tawil shared cases of individuals who were sent back to Syria “either by the Lebanese government or after being kidnapped by Hezbollah,” detailing the journey of a group of Syrians looking to go to Turkey by sea.

“The captain was with Hezbollah, so he drove them instead to the Syrian port city of Latakia, where they were handed to Syrian Security,” said Tawil. “One of them was my friend; he was a pharmacist and activist. His family received his dead body one week later.”

Beyond Safety Concerns: Issues In Freedom, Legality, and Economic Independence

When they arrive to Lebanon, exiled journalists are not free to cover a number of sensitive topics including but not limited to politics, religion, prisoners and kidnappings. The Lebanese State Security, one of the four main intelligence and security apparatuses in Lebanon, has recurrently threatened journalists who dare to cover these subjects.

Such was the case, among others, for the Syrian journalist Abdelhafiz Al Houlani. According to the Syrian Journalists Association, he was detained on November 19, 2018 after reporting on cases of abnormal abortions in the Arsal refugee camp in North Lebanon.

Among others, SKeyes Executive Director Ayman Mhanna highlights the legal issues related to residency and work permit.

“Getting the paperwork done to be able to work legally in the country can be quite expensive and slow,” he explains. Ahmad Alqusair obtained his residency permit one year after his arrival. Consequently, many journalists who legally enter the country could easily end up working without documentation.

The presence of an anti-refugee climate unsurprisingly constitutes an additional source of vulnerability for exiled journalists in Lebanon.

“The official discourse of Lebanese authorities is very much against refugees,” said Mhanna.

Among all these elements, it is worth mentioning the financial pressure on exiled journalists in Lebanon. In a country that is also facing a severe economic crisis, media outlets often lack enough funds to pay livable salaries to their employees.

Exploring the many facets of freedom of the press, in a country that is traditionally perceived as more liberal compared to the surrounding area, exposes its intricacies. For Syrians, their safety concerns exponentially increase. For exiled journalists in Lebanon in general, their legal status, financial independence and the increasing anti-refugee climate stand as major concerns.

As a result, exiled journalists who were forced to leave their country of origins for their work do not wish to settle in the country. Lebanon represents but a step in their long pursuit for a place where they can continue to seek and report the truth freely, independently and safely.