The “People’s Budget” series is a set of articles that reflect the opinions of economists and other experts regarding the most recent updates on Lebanon’s 2019 draft budget.

Lebanon’s newest government, after taking 252 days to be formed, is now supposed to come up with a budget for 2019. The ruling politicians have declared it an “austerity budget” where “substantive reductions in spending” would be enacted, and where all economic stakeholders would be expected to make “collective painful concessions.” This discourse is unacceptable. The ruling class, which has been in power for almost 30 years, is collectively responsible for the economy’s dire state of affairs. It should bear the costs of reforms and spare ordinary citizens.

It is time for a people’s budget that reflects the priorities of citizens and upholds their well-being.

The current budget composition, in terms of public spending and revenues, reflects decades of mismanagement of public affairs, and represents the economic and financial interests and priorities of the ruling class. Yet listening to or reading recent statements made by public officials gives an impression that the ruling class either inherited the economic woes from an unknown predecessor, or that some alien ghost was making decisions.

These tactics to dilute responsibility and divert public opinion are no longer a secret to anyone. Lebanon’s rulers have always felt they could get away with anything, continuously benefiting from an international community that favors stability and security over proper governance and accountability, as well as a local population exacerbated by decades of conflict and both social and economic insecurity. But the people have called their bluff.

How the ruling class controls and allocates the budget

Lebanon’s rulers have devised many tricks to maintain their grip on the budget. First, they avoided any public oversight and democratic control of public money, even by their own elected members of parliament. For 12 years, between 2005 and 2017, the government spent funds and collected taxes without any official budget submitted and approved by Parliament. The official Ministry of Finance accounts for these 12 years have not yet been submitted for approval by the Council of Ministers and Parliament.

Today, the government still operates based on substantive treasury advances in the form of cash loans to ministries and public agencies “until a budget is approved.” Just last month, Parliament authorized the government to issue new debt for almost $5 billion to pay for arrears and accumulated dues, without a budget and with no official accounts submitted.

On top of this, to date public agencies –like Electricite du Liban and OGERO (the state telecom provider)– and autonomous funds –like the High Commission For Relief, the Council of the South, the Fund for the Displaced and many others– operate outside Parliament control, and are still not covered by the central government’s budget process. Together they represent an estimated 20 percent of total public spending, a sizeable amount concealed in a legal black box.

This situation has provided the ruling class with the opportunity to infiltrate and control these entities, with substantive fiscal implications on taxpayers’ money and a degradation of public services due to nepotism and lack of oversight. The recent scandal related to over-recruitment in public agencies and “ghost civil servants” only confirms this assessment.

Within the budget, Lebanon’s rulers have resorted to increasing public sector hiring especially in security services to strengthen their grip on their respective communities and to provide a quick solution to rising unemployment, especially among the youth. Public wages and benefits now constitute more than 35 percent of government spending. In parallel, the ruling class allowed the public electricity provider to sustain losses over decades, as they benefited from this situation through the oil importing and the private generator cartels that they control. Almost 10 percent of the government’s budget is spent yearly as a subsidy for EDL, mainly to cover expensive fuel oil imports and perpetual losses made by the opaque and unaccountable company.

Other current government expenses, again not controlled or audited by anyone, have been allocated to various expenses like donations to non-governmental organizations (close to the ruling class), trips and conferences, over-budgeted office supplies and stationary, public function cars, and other types of wasteful spending. All of these constitute an estimated 5 percent of public expenses, about $800 million that could easily be reduced. Other main expenditure items include capital expenses, other subsidies and other expenses, which amount to around 18 percent of total expenditure. The remaining budget, more than a third of it, goes to pay interest on debt.

On the revenues side, the ruling class has historically minimized taxes imposed on the financial and real estate sectors –and on companies in general– given the close ties politicians have maintained with the main dominant stakeholders in the country’s banking, real estate, hospitality and trade sectors.

Instead, politicians resorted to increasing indirect consumption-based taxes like the Value Added Tax (VAT) and customs duties, as well as maintaining extremely high tariffs on telecom charges. Currently direct taxes constitute less than 35 percent of the nearly $11 billion in total public revenues.

| Public revenues breakdown, 2017 | Million US$ | Share of total revenues |

| Direct taxes | 3,743 | 35% |

| Profits tax – banks | 500 | 5% |

| Income and profits tax – other sector | 901 | 8% |

| Tax on deposit interest income | 603 | 6% |

| Other revenue and payroll taxes | 798 | 7% |

| Taxes on property | 942 | 9% |

| Indirect taxes | 4,512 | 42% |

| Customs | 1,442 | 13% |

| VAT | 2,317 | 21% |

| Other tax revenues | 752 | 7% |

| Non-tax revenues | 2,578 | 24% |

| Telecom revenues | 1,291 | 12% |

| Other non-tax revenue | 1,287 | 12% |

| Total | 10,832 | 100% |

Compiled by Dr. Jad Chaaban based on MoF 2018 data

The 2019 Government’s budget “plans”

With more than $16 billion in expenses and only around $11 billion in revenues, the deficit would reach at least $5 billion in 2019.

To reduce it, the ruling class is currently promoting a rhetoric that say the debt interest portion of the budget should not be touched since it would affect foreign debtors’ confidence. They are also saying that some essential spending could not be altered, like capital and investment spending on infrastructure. As such, their rhetoric suggests that the only components that should be reduced are the electricity subsidy, the wasteful current expenses, and wages and benefits of public sector workers.

These three components represent about 50 percent of the government budget.

In parallel, the government is once again contemplating an increase of indirect taxes including VAT from 11 percent to 15 percent, the taxation of benzene, and a reduction of tax evasion.

Electricity subsidy expenses might be reduced, but not this year:

It seems that the reduction in the electricity subsidy has finally been put on track. The new plan to reform the electricity sector and reduce the electricity subsidy has been successfully enacted this month, after an agreement among the ruling parties despite several setbacks in the new legislation linked to the energy sector’s governance and the bypass of proper public procurement practices.

All in all, the impact on the state budget of these reforms would not be felt before at least another year as most electricity generation investment projects require several months to be implemented.

Reducing public sector wages and benefits will drive thousands into poverty:

In 2017 and following more than a decade without any increase, the government approved a new pay structure and an increase in public sector wages after civil servants lost more than 80 percent of their salaries’ purchasing power due to inflation. Public sector pensioners were also given their increase in installments over a period of three years.

Depriving civil servants from their vested right to a dignified salary is unacceptable, and politically short-sighted. In the absence of universal health coverage and quality free public education, many civil servants rely on their jobs as safety nets in a country where everything has become privatized and very expensive.

Simulations undertaken by the American University of Beirut’s Applied Economics and Development Research Group have estimated that poverty among individuals living in families having public sector employees would increase by almost 40 percent following a wage reduction of 10 percent. This would translate into more than 50,000 newly impoverished individuals as a result of this decrease.

Poverty incidence estimates following decrease in public sector wages by 10 percent

| Total Lebanese Population | Individuals in families with at least one public sector employee | Individuals in families with at least one public sector employee After 10% reduction in wages |

|

| Not Poor | 65% | 73% | 63% |

| Poor | 35% | 27% | 37% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Source: AUB Applied Economics and Development Research Group, based on households’ expenditure survey data collected in 2016.

Increasing indirect taxes like the VAT and benzene tax would push many Lebanese into poverty:

The argument that the current VAT system has many exemptions on essential food and non-food commodities does not hold since the VAT enters into the cost of many traders and producers, who factor its increases in their final products pricing.

The absence of reliable public transportation would make any increase in benzene prices extremely hurtful for consumers and producers alike. Simulations undertaken by the American University of Beirut’s Applied Economics and Development Research Group have estimated that around 90,000 individuals would fall into poverty following the planned increases in VAT and benzene tax.

Towards A People’s Budget: Reforms that would put people’s interests first

In order to regain citizens’ trust, reforms to the government’s budget should prioritize three main pillars: accountability, social justice, and realistic feasibility. For accountability, public finances should be submitted with all needed past comprehensive accounts. For social justice, reforms should prioritize the targeting of the very wealthy and avoid indirect regressive taxes. For realistic feasibility, reforms should be realistic and feasible in the medium term, and not involve promises that are too idealistic given the country’s political divisions and entrenched corruption.

For the 2019 budget, on top of the electricity subsidy reduction plan already put into effect, the following measures could be enacted along the principles outlined above:

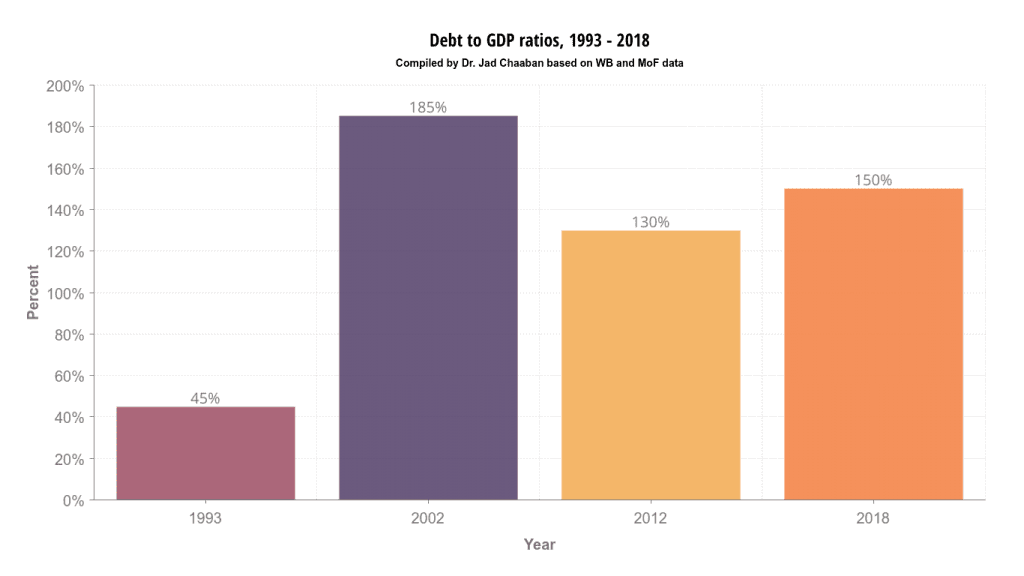

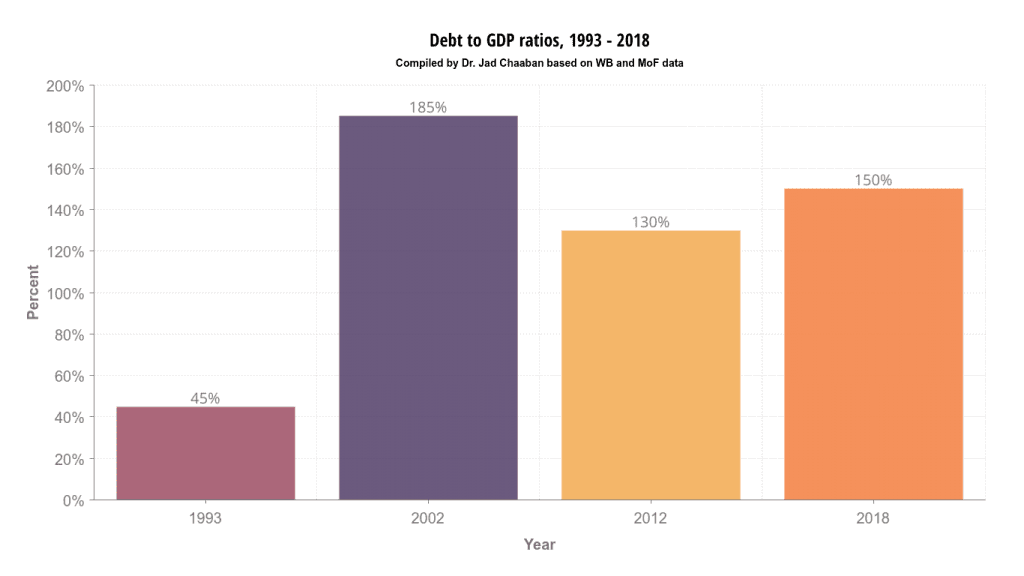

1. Reduce public debt service by implementing a special scheme, similar to 2002, with the Central Bank and commercial banks:

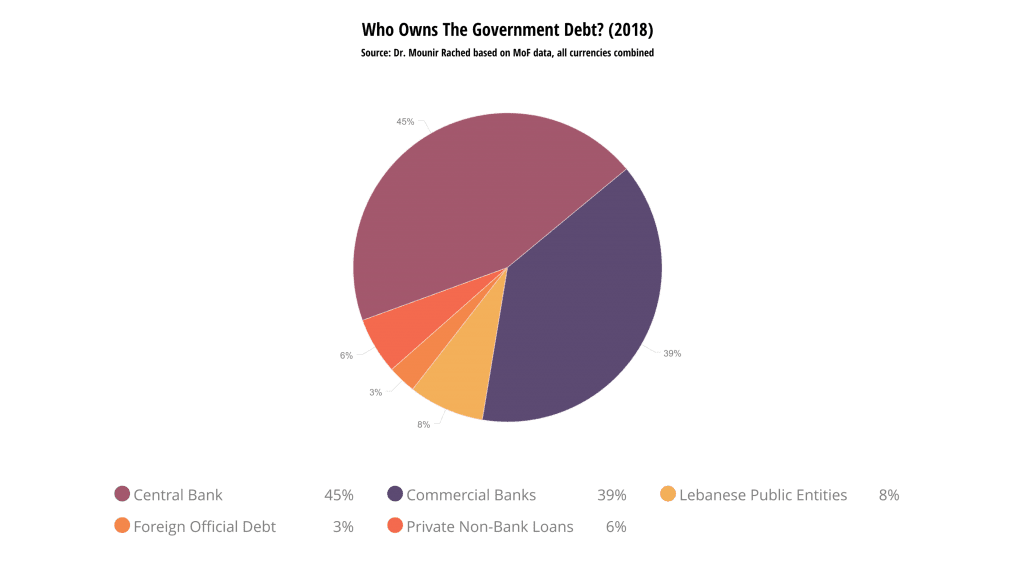

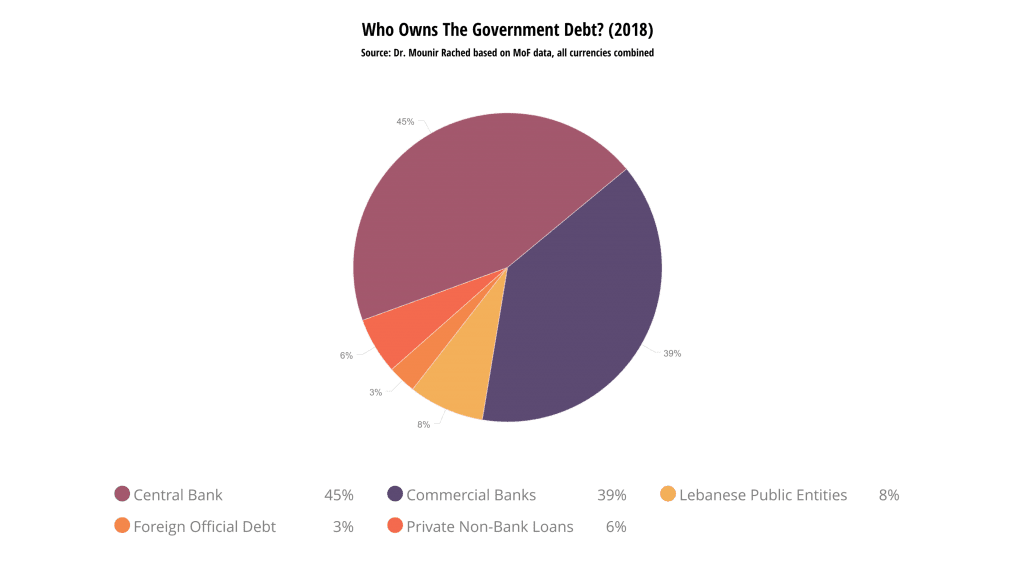

In 2018, 55 percent of public debt was in Lebanese pounds, and 92 percent of the total debt in all currencies was held by local institutions –the Central Bank, commercial banks and Lebanese public entities.

In the equivalent amount of $ 4.1 billion, the first scheme consisted of:

- The cancellation of the equivalent of $1.8 billion of BDL’s Lebanese Pound Treasury bills portfolio against reserves, due to the Lebanese Treasury as per Article 115 of the Code of Money and Credit.

- The exchange of the equivalent of $1.9 billion of BDL’s Lebanese Pounds Treasury bills, Eurobonds, and accrued interest for new debt with longer maturity –15 years– and lower interest at 4 percent.

- The rollover of $0.4 billion of principal and interest on maturing Treasury bills held by BDL via a new issue of 5-year, 4 percent special Treasury bills in July 2003.

The second scheme, in the equivalent amount of $3.6 billion, was concluded with the Lebanese commercial banks, and involved a voluntary supply of two-year, zero interest financing to the government.

The Central Bank has been, for several years now, undertaking debt exchange and roll over with the Ministry of Finance by exchanging short term government debt it holds with longer term maturities. But debt cancellation was not on the table, and could be considered similar to 2002.

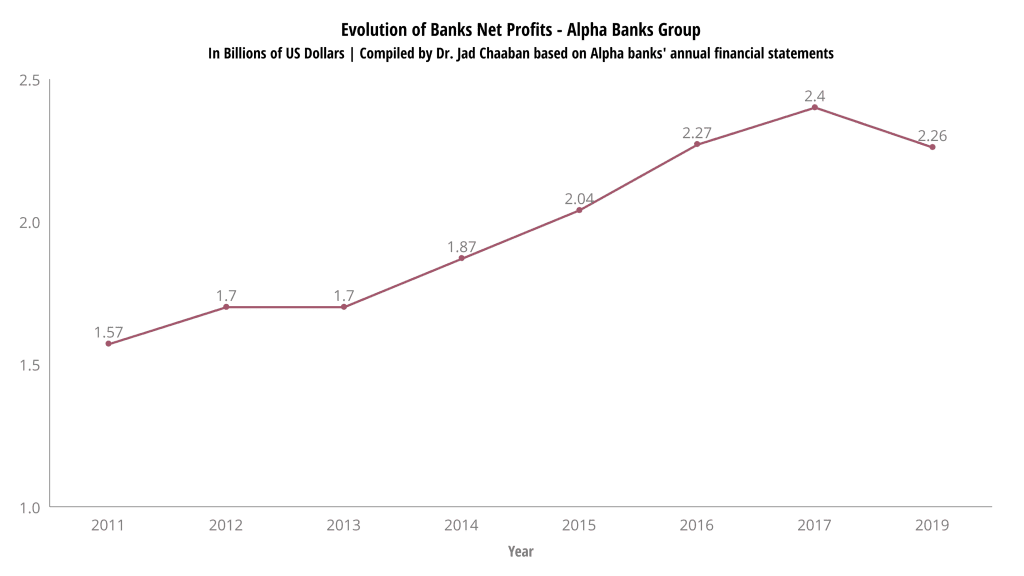

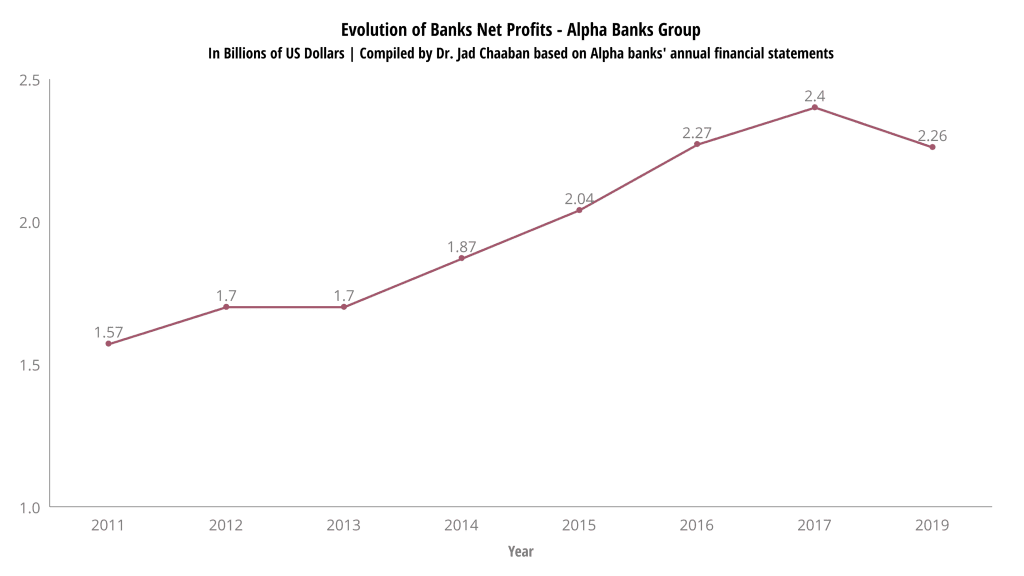

On the banks side, the top 14 commercial banks –known as the Alpha group banks– have witnessed an average 7 percent increase in their net profits every year since 2011 despite the country’s GDP stalling over the same period and many other sectors suffering.

It is therefore more than fair to request that they contribute more than others to help balance the public budget by accepting 0-interest bearing treasury bills for a period of two years, similar to what they did in 2002.

2. Increase taxes on bank deposits interest income from 7 percent to 11 percent on accounts with more than $1 million:

Bank deposits in Lebanon are highly concentrated. The IMF estimated that, as of late 2015, the largest 1 percent of deposit accounts hold 50 percent of total deposits, while the largest 0.1 percent of accounts hold 20 percent of total deposits.

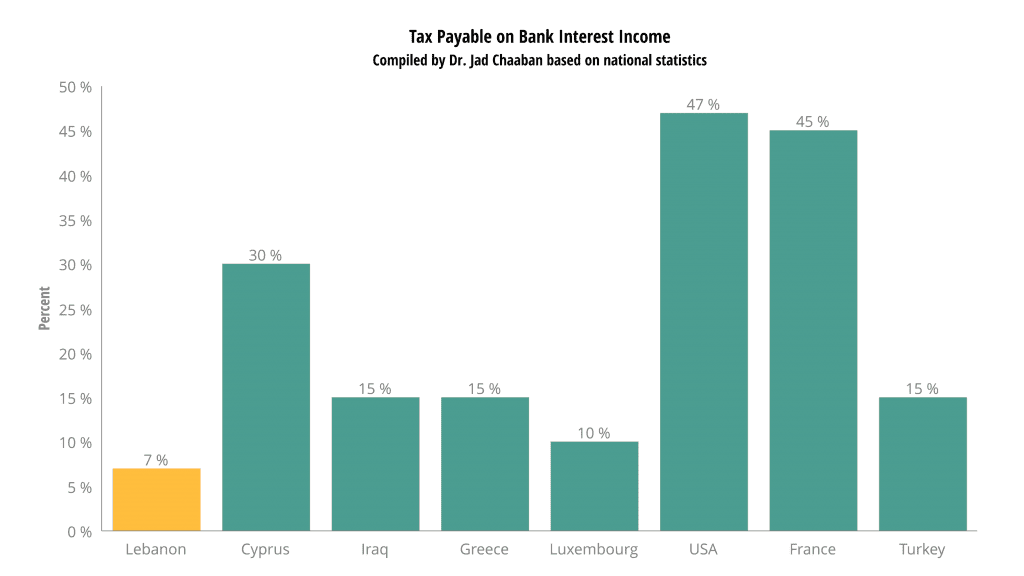

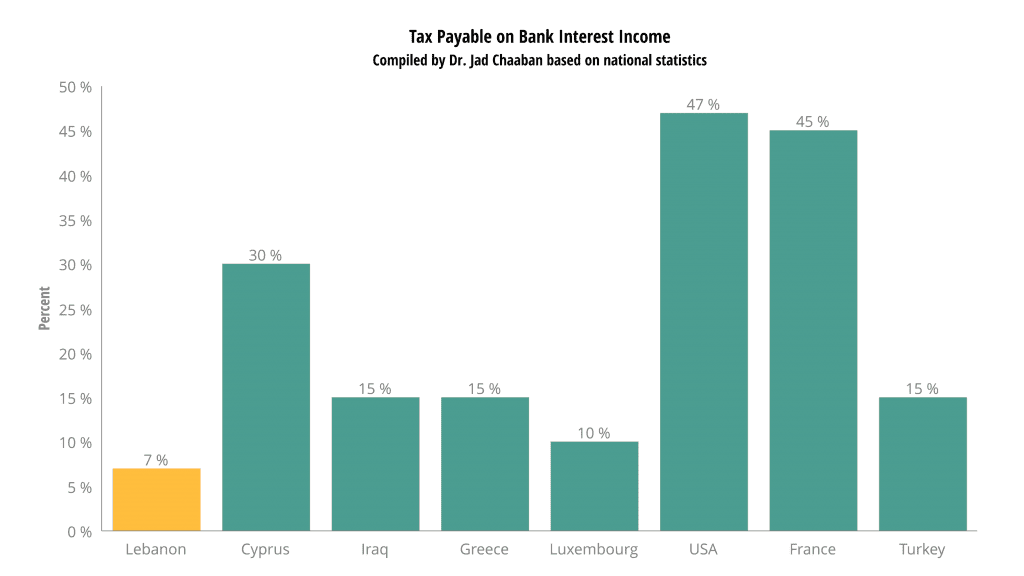

In 2017, the government increased taxes on interest income on deposits from 5 percent to 7 percent but did not distinguish between small savings accounts and large very rich depositors. Even with this increase, the tax of 7 percent on interest income remains one of the lowest in the region and the world –it’s 15 percent in Turkey and Iraq, 30 percent in Cyprus, and 47 percent in the US.

The government could increase taxes on interest income from 7 percent to 11 percent on large deposit accounts that have more than $1 million in deposits, and avoid increasing on small depositors since there is a very high concentration of accounts in the hands of the 1 percent.